Do you know what the Little Mermaid, Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter have in common? No, it’s not an irritating protagonist, although this might be true. It is the monomyth, also known as the hero’s journey. It is a narrative structure widely used in fiction and, of course, myths such as that of Perseus. If you look carefully, these stories – and a lot of others – have exactly the same framework.

The term ‘monomyth’ was first described by Joseph Campbell in his book “The Hero with a Thousand Faces”. Campbell borrowed the term from one of the works of James Joyce, called Finnegan’s Wake. The monomyth is divided into three acts: departure, initiation and return. Each of them has subchapters, such as the everyday world and the so-called Call to Adventure, Road of Trials, the moment where all is lost, the apotheosis and return.

It may or may not be because Ireland boasts some of the world’s most important writers, like Joyce incidentally, but Irish whiskey, over the centuries, traces a similar path to that of the monomyth. From the monastery gates to glory and subsequent decline, to being reborn and retaking its place in the world, Irish whiskey is a true Perseus of drinks, facing ethylic gods. I’m going to explain its journey here in two parts. Prepare yourself, dear reader, for an ethylic Lord of the Rings, without the irritating hobbit.

Our journey begins on the Iberian Peninsula. The process of alcohol distillation – formerly rather rudimentary – was being perfected by Arabian alchemists of the eighth century in Spain. It was here that what can be considered the first still was used. In time, the technique was to be passed on to Christian monks from various European countries and taken by them to Ireland and Scotland during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Although there is no historical document that proves this theory, Ireland was probably the first place to produce whiskey. It was the island of choice to house Christian monks, who had escaped from barbarian invasions in other European countries. Irish missionaries led by the, currently world famous, Saint Patrick would have settled in the country, bringing the technique they learned from the Arabs on the Iberian Peninsula, to produce the best drink in the world. Following this theory, whiskey would have been brought to England and Scotland when King Henry II invaded Ireland and met his fearlessly intoxicated foes.

Incidentally, the word “whiskey” is an anglicised reduction of the expression ‘uisge beatha’, which literally means ‘water of life’. The monks who produced the distillate believed it possessed medicinal and healing properties. They believed it could be used to prolong life and improve simple evils like stomach ache, smallpox and the incurable existential boredom of life in a wet, cold place with no television, internet, smartphones or cinemas…

Whiskey might have been produced exclusively in monasteries for a long time, had it not been for King Henry VIII and his Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536. The suppression was a set of administrative and legal rules that ordered the dissolution of the places and the appropriation of their assets and revenues. This is where our hero, Irish Whiskey, begins his journey. The call to adventure and the abandonment of the everyday world. Here, there was no room for inhibition or fear.

With the King’s orders as they were, the Christian monks had to turn to something that could only be described today as a private initiative. They were forced to produce whiskey on their own, outside the seclusion of the monasteries. But something not-so-unexpected (since we’re talking about whisky) happened: The popularity of the drink grew enormously.

During the sixteenth century, distillery after distillery appeared. It is estimated that there were over two hundred whiskey distilleries in Ireland at the turn of the seventeenth century. Curiously, at the time Irish whiskey was known as a refined product and Scottish whisky was considered unhinged and crude.

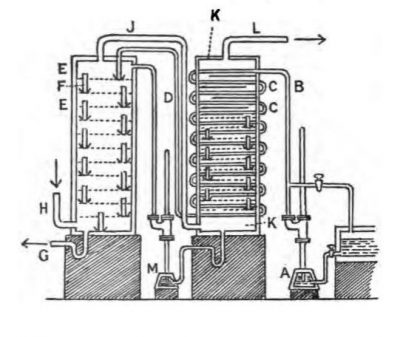

However, our hero’s path is littered with difficulties. The first of them, incredible as it may seem, was friendly fire: The invention of the continuous distiller by an Irishman, Sir Anthony Perrier. The invention, somewhat rudimentary at first, was improved by the Scotsman Robert Stein, and later perfected by another Irishman, Aeneas Coffey, an Irish taxman, who specialised in alcoholic beverage taxation.

The continuous distiller – known as the Coffey Still – allowed Scotland to create a new class of whiskies: The blended Scotch whisky. By putting their heavy, oily malts together with the light distillate of the continuous distillers, the Scots produced an extremely palatable product whose production method cost just a fraction of the Irish method (distillation in stills). Efficient production, coupled with the endless marketing efforts of the Scottish, has significantly reduced worldwide consumption of Irish whiskey.

In 1919, Ireland separated from the United Kingdom and gained its independence. It was an important historical event but caused instability for Irish whiskey. Independence made Ireland’s access to the lucrative markets of the British empire more difficult. To make matters worse, the Irish government, which considered the distilleries favourable to the crown, imposed heavy taxes on the drink, making it expensive even in Ireland.

Add to that the fact that Irish whiskey was imported in bulk, inside barrels and bottled and cut at its destination. This practice, although economically advantageous, made falsification and tampering easier. Scotch whisky, on the other hand, was imported in bottles making this pretty difficult to reproduce.

However, all was not lost. Our protagonist still walked with his head held high, despite the latest events. After all, Irish whiskey was still well-known in the USA. Well, it was until the fateful year of 1919, when the Volstead Act – better known as the Prohibition Act – was passed and with it the biggest Irish whiskey market in the world vanished.

There was our hero, in his all-is-lost moment. There was no hope. The Prohibition Act had undermined any chance of survival for the spirit that was once considered one of the most beloved in the world. Down-trodden by Scotch whisky, inhibited by the Irish government and rejected by the USA, there was nothing left. The years whittled away and one by one the Irish distilleries began to close. In 1960, from the hundreds, there were only five remaining: Corelaine, Bushmills, Jameson, Cork Distilleries and John Power & Sons.

Desperate for survival many distilleries joined forces. In 1966, Jameson, Cork and John Powers merged forming the Irish justice (or ethylic) league, called Irish Distiller’s Limited. In 1975, the three halted production transferring it to a single plant in Cork, which would later become the world-renowned Midleton. The following year, Colaraine closed its doors and Bushmill’s became the only producer of Irish whiskey, located in Northern Ireland, despite all this consumption of Irish whiskey continued to fall.

But in 1987 something remarkable happened. A gentleman named John Teeling acquired a chemical distillery – Ceimici Teoranta – with column distillers and he installed two stills there. He then renamed the plant Cooley Distillery. The first new Irish distillery in over a century was born. At the same time Pernod-Ricard showed an interest in Irish Distiller’s Limited. The acquisition, which took place in 1988, put Irish whiskey back on the international market and raised Jameson to unprecedented fame.

Our distilled hero had reached his apotheosis. With Pernod Ricard’s resurrection of Midleton, investors took more kindly to the whiskey. By 2016 seventeen distilleries had opened, some more rustic, like Dingle, and others much larger. Midleton itself, noting the sudden growth of its product, invested more than one hundred million to double production capacity in that same year.

Pernod was not the only giant to turn its attention to Irish whiskey. A Diageo bought Bushmills in 2013. William Grang and Sons – the name Family empire behind the Scottish Glenfiddich, Balvenie, Kininvie and Ailsa Bay – acquired, expanded and modernised the huge Tullamore D.E.W. The year before Jim Beam, the current Beam Suntory, took over the pioneer Cooley.

In 2018, the number of distilleries is still growing. There are eighteen in operation (although some haven’t released products into the market yet) and another sixteen are being planned, according to the Irish whiskey Association. In the light of such numbers, it is undeniable that Irish whiskey is in an important phase of resurgence and rediscovery – The Irish whiskey Renaissance.

Another sector indirectly encouraged by the revival of Irish whiskey is tourism. In 2016, six hundred and fifty thousand people visited distilleries with visitor centres and this number is set to rise. Now, that are hero numbers, are not they?