Aultmore 21 – Optimism

When I was five years old, I remember a visit I made to the pediatrician. He measured my foot, then the circumference of my head. With the smile of a child who has just discovered a confidence, he said resolutely that I would be six feet tall and strong as a pit bull. And then, thirty years later, I remembered this story, from the top of my disproportionate head, fixed on a body that is more like a dachshund, four feet off the ground.

But I wasn’t the only one to be lulled into prophecies of gigantism by pediatricians. It’s kind of a rule – you’ll always stay six feet tall, play basketball with the agility of a marmoset and have the bone mass of a brachiosaurus. But decades later, you end up puny, with mediocre stature, feet that look like two rackets, and bones pushing the skin in the wrong places. Pediatricians are naturally optimistic.

I think it’s a matter of human nature’s expectation. You expect the future to be extraordinary. It’s like, for example, when I open a whisky that I’ve never had in my life – Aultmore 21 years old, for example, which has just officially arrived in Brazil. The unopened bottle promises an incredible, poignant, distinct experience. Totally out of the curve. Even more so for very exclusive and mature whiskies. But, unfortunately, this expectation is not always met.

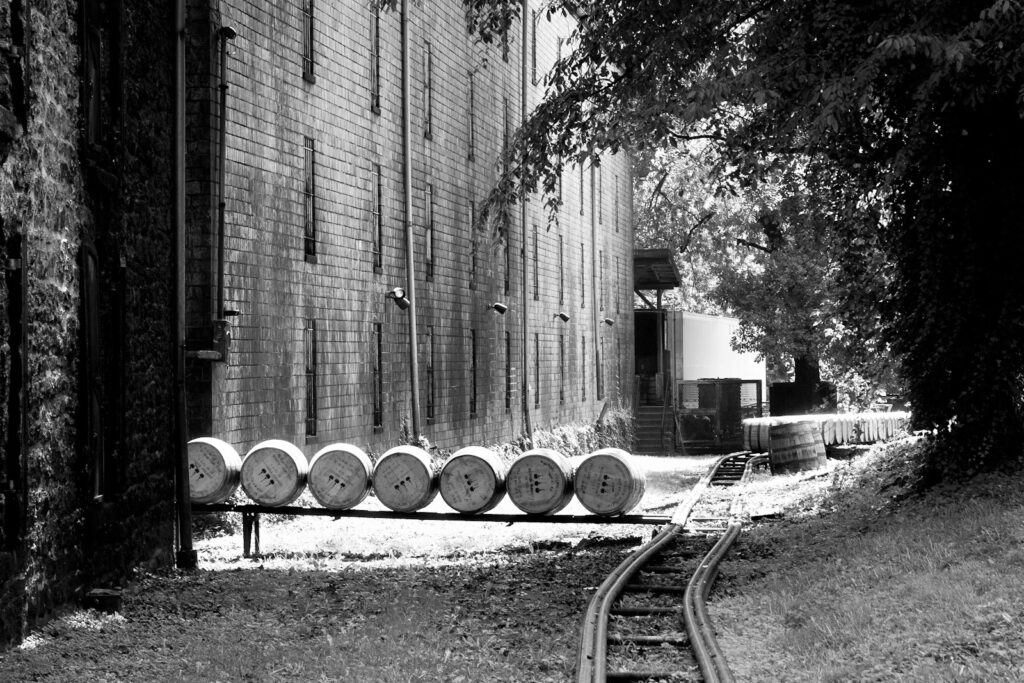

I’ll start by contextualizing. While Aultmore’s story is a survival story – it lived on through the Pattinson crisis, the Volstead Act, the Great Depression and the two world wars – it never really shone on its own, as did some of its celebrated neighbors. Instead. His role has always been backstage – Aultmore is an important ingredient for blended scotches, especially the Dewar’s range.

Aultmore is located in the Moray Mountains, north of Keith, next to a road called Buckie Road – locally, they ask for a “a wee dram of the Buckie Road”. It is difficult to access and sparsely populated. Next to the distillery is an area known as the Foggie Moss, which at the time of Aultmore’s founding was quite rich in peat. These conditions, together with the ease of obtaining water, made the Aultmore region quite famous among illicit distillers in the mid-nineteenth century.

Aultmore’s supporting role changed when Bacardi, its owner, decided to launch in 2014 a series of bottlings of its distilleries – the well-known and modestly named “The Last Great Malts of Scotland” – highlighting Aberfeldy and the delicious Royal Brackla. Among them was also the Aultmore 21 years. Originally designed for the duty-free market, this expression is now also sold in selected domestic markets around the world – I suspect, due to COVID. Including Brazil.

Aultmore 21 years is a premium single malt, with a profile that refers to a blended luxury whisky. It’s quite complex – there’s honey, caramel, vanilla, creme brulee and a vegetable, herbaceous note. But it’s also a delicate and balanced whisky. The time – the ages in the cask – here brought softness, not intensity. There are no sharp edges or any aggressiveness. And that’s where the maturation, which happens in refill hogsheads, becomes apparent.

The smoothness of maturation also finds balance in its spirit, which has a medium body. Aultmore stills are low, which prevents reflux. However, the distillation is slow and encourages reflux, making the drink more aromatic and less oily. The distillate does not undergo cold filtration, and there is no added caramel coloring – the color is totally natural.

With that description, the 21 year old Aultmore sounds like an extraordinary liquid. And, as a matter of fact, he really is. But maybe it takes some experience to understand its greatness. It is a single malt with more than two decades of maturation, but whose sensory profile is close to an ultra-luxury blended scotch whisey. A delicate and complex whisky, balanced, without peat and herbal.

And maybe I was the one who was wrong in the expectation, and the problem is there, not in the liquid. Because in Brazil, a bottle of Aultmore 21 years costs a little more than a thousand reais. It’s a great price for a 21 year old single malt (that’s what it is!). However, it is perhaps an adequate price at the most considering a whisky which flavour profile is close to an ultra-luxury blend. Whose objective, by the way, is exactly the same – to bring complexity and smooth.

So my recommendation here will be twofold. Whether you’re passionate about smooth and delicate whiskies, or ultra-luxury blended scotch whiskies that combine complexity and smoothness, like the 25-year-old Dewar’s, the Aultmore 21 will be a perfect single malt for your taste buds. But, align your expectations – except, of course, if you’re a pediatrician.

AULTMORE 21

Type: Single malt

Distillery: Aultmore

Region: Speyside

ABV: 46%

TASTING NOTES

Aroma: Floral, citrus, herbs (as always, the legal ones…).

Taste: Herbaceous. grassy, slightly citrus. Honey, caramel, creme brulee. Medium and sweet finish.

*the bottle of the whisky subject of this tasting was provided by third parties involved in its production. This Dog, however, maintained complete editorial freedom over the content of the post.